Grey wolf genomic history reveals a dual ancestry of dogs

書誌情報Bergström, A., Stanton, D.W.G., Taron, U.H. et al. Grey wolf genomic history reveals a dual ancestry of dogs. Nature 607, 313–320 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04824-9

表題の論文を日本語訳してみました。翻訳アプリにかけた日本語訳を英文に照らして修正していますが、表記のゆれや訳の間違いがあるかもしれません。正確に内容を知りたい方は、原文をご覧ください。

Abstract:要旨

The grey wolf (Canis lupus) was the first species to give rise to a domestic population, and they remained widespread throughout the last Ice Age when many other large mammal species went extinct.

ハイイロオオカミ(Canis lupus)は家畜として飼われるようになった最初の種であり、他の多くの大型哺乳類が絶滅した最後の氷河期を通じて広く生息していた。

Little is known, however, about the history and possible extinction of past wolf populations or when and where the wolf progenitors of the present-day dog lineage (Canis familiaris) lived.

しかし、過去のオオカミ個体群の歴史や絶滅の可能性、あるいは現在のイヌ科(Canis familiaris)の祖先となるオオカミがいつどこで暮らしていたのかについては、ほとんどわかっていない。

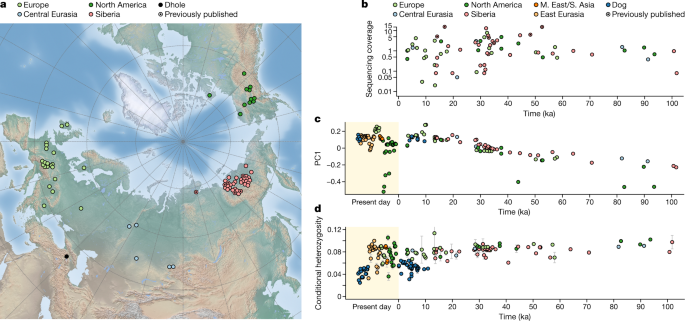

Here we analysed 72 ancient wolf genomes spanning the last 100,000 years from Europe, Siberia and North America.

ここではヨーロッパ、シベリア、北アメリカから過去10万年にわたる72の古代オオカミゲノムを分析した。

We found that wolf populations were highly connected throughout the Late Pleistocene, with levels of differentiation an order of magnitude lower than they are today.

私たちは、オオカミの個体群は後期更新世を通じて高度に連結しており、分化のレベルは現在よりも桁違いに低いことを発見した。

This population connectivity allowed us to detect natural selection across the time series, including rapid fixation of mutations in the gene IFT88 40,000–30,000 years ago.

この集団の連結性によって、4万~3万年前のIFT88遺伝子の突然変異の急速な固定化など、時系列にわたる自然選択を検出することができた。

We show that dogs are overall more closely related to ancient wolves from eastern Eurasia than to those from western Eurasia, suggesting a domestication process in the east.

我々は、イヌは全体的に西ユーラシアのオオカミよりも東ユーラシアの古代のオオカミに近縁であることを示しており、これは東方での家畜化の過程を示唆している。

However, we also found that dogs in the Near East and Africa derive up to half of their ancestry from a distinct population related to modern southwest Eurasian wolves, reflecting either an independent domestication process or admixture from local wolves.

しかし、我々はまた、近東とアフリカのイヌが、祖先の最大半分を現代のユーラシア南西部のオオカミに関連する別個の集団に由来することを発見した。これは、独立した家畜化の過程か、地元のオオカミからの混血を反映している。

None of the analysed ancient wolf genomes is a direct match for either of these dog ancestries, meaning that the exact progenitor populations remain to be located.

分析された古代のオオカミのゲノムはいずれもこれらのイヌの祖先と直接一致しなかった。

References:参考文献

Savolainen, P., Zhang, Y.-P., Luo, J., Lundeberg, J. & Leitner, T. Genetic evidence for an East Asian origin of domestic dogs. Science 298, 1610–1613 (2002).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google ScholarWang, G.-D. et al. Out of southern East Asia: the natural history of domestic dogs across the world. Cell Res. 26, 21–33 (2016).

Article PubMed Google ScholarFrantz, L. A. F. et al. Genomic and archaeological evidence suggest a dual origin of domestic dogs. Science 352, 1228–1231 (2016).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google ScholarShannon, L. M. et al. Genetic structure in village dogs reveals a Central Asian domestication origin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13639–13644 (2015).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarThalmann, O. et al. Complete mitochondrial genomes of ancient canids suggest a European origin of domestic dogs. Science 342, 871–874 (2013).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google ScholarVonholdt, B. M. et al. Genome-wide SNP and haplotype analyses reveal a rich history underlying dog domestication. Nature 464, 898–902 (2010).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarBotigué, L. R. et al. Ancient European dog genomes reveal continuity since the Early Neolithic. Nat. Commun. 8, 16082 (2017).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarBergström, A. et al. Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs. Science 370, 557–564 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarTian, H. et al. Intraflagellar transport 88 (IFT88) is crucial for craniofacial development in mice and is a candidate gene for human cleft lip and palate. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 860–872 (2017).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarFan, Z. et al. Worldwide patterns of genomic variation and admixture in gray wolves. Genome Res. 26, 163–173 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarvonHoldt, B. M. et al. Whole-genome sequence analysis shows that two endemic species of North American wolf are admixtures of the coyote and gray wolf. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501714 (2016).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarHughes, P. D. & Gibbard, P. L. A stratigraphical basis for the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). Quat. Int. 383, 174–185 (2015).

Article Google ScholarSkoglund, P., Ersmark, E., Palkopoulou, E. & Dalén, L. Ancient wolf genome reveals an early divergence of domestic dog ancestors and admixture into high-latitude breeds. Curr. Biol. 25, 1515–1519 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarRamos-Madrigal, J. et al. Genomes of Pleistocene Siberian wolves uncover multiple extinct wolf lineages. Curr. Biol. 31, 198–206 (2020).

Article PubMed Google ScholarJanssens, L. et al. A new look at an old dog: Bonn-Oberkassel reconsidered. J. Archaeol. Sci. 92, 126–138 (2018).

Article Google ScholarPerri, A. R. et al. Dog domestication and the dual dispersal of people and dogs into the Americas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2010083118 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarSinding, M.-H. S. et al. Arctic-adapted dogs emerged at the Pleistocene–Holocene transition. Science 368, 1495–1499 (2020).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarPečnerová, P. et al. Genome-based sexing provides clues about behavior and social structure in the woolly mammoth. Curr. Biol. 27, 3505–3510 (2017).

Article PubMed Google ScholarGower, G. et al. Widespread male sex bias in mammal fossil and museum collections. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19019–19024 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarDrummond, A. J. & Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 214 (2007).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarLoog, L. et al. Ancient DNA suggests modern wolves trace their origin to a Late Pleistocene expansion from Beringia. Mol. Ecol. 29, 1596–1610 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarGopalakrishnan, S. et al. Interspecific gene flow shaped the evolution of the genus Canis. Curr. Biol. 28, 3441–3449 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarWang, M.-S. et al. Ancient hybridization with an unknown population facilitated high-altitude adaptation of canids. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 2616–2629 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarvonHoldt, B. M. et al. A genome-wide perspective on the evolutionary history of enigmatic wolf-like canids. Genome Res. 21, 1294–1305 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarSinding, M.-H. S. et al. Population genomics of grey wolves and wolf-like canids in North America. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007745 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarWang, K., Mathieson, I., O’Connell, J. & Schiffels, S. Tracking human population structure through time from whole genome sequences. PLoS Genet. 16, e1008552 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarKurtén, B. & Anderson, E. Pleistocene Mammals of North America (Columbia University Press, 1980).

Hu, A. et al. Influence of Bering Strait flow and North Atlantic circulation on glacial sea-level changes. Nat. Geosci. 3, 118–121 (2010).

Article ADS CAS Google ScholarVershinina, A. O. et al. Ancient horse genomes reveal the timing and extent of dispersals across the Bering Land Bridge. Mol. Ecol. 30, 6144–6161 (2021).

Article PubMed Google ScholarLeonard, J. A. et al. Megafaunal extinctions and the disappearance of a specialized wolf ecomorph. Curr. Biol. 17, 1146–1150 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarHudson, R. R., Slatkin, M. & Maddison, W. P. Estimation of levels of gene flow from DNA sequence data. Genetics 132, 583–589 (1992).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarPilot, M. et al. Genome-wide signatures of population bottlenecks and diversifying selection in European wolves. Heredity 112, 428–442 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarDufresnes, C. et al. Howling from the past: historical phylogeography and diversity losses in European grey wolves. Proc. Biol. Sci. 285, 20181148 (2018).

PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarDevlin, B. & Roeder, K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics 55, 997–1004 (1999).

Article CAS PubMed MATH Google ScholarSpeidel, L., Forest, M., Shi, S. & Myers, S. R. A method for genome-wide genealogy estimation for thousands of samples. Nat. Genet. 51, 1321–1329 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarStern, A. J., Wilton, P. R. & Nielsen, R. An approximate full-likelihood method for inferring selection and allele frequency trajectories from DNA sequence data. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008384 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarFreedman, A. H. et al. Genome sequencing highlights the dynamic early history of dogs. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004016 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarRimbault, M. et al. Derived variants at six genes explain nearly half of size reduction in dog breeds. Genome Res. 23, 1985–1995 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarWebster, M. T. et al. Linked genetic variants on chromosome 10 control ear morphology and body mass among dog breeds. BMC Genomics 16, 474 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarPlassais, J. et al. Whole genome sequencing of canids reveals genomic regions under selection and variants influencing morphology. Nat. Commun. 10, 1489 (2019).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarBoyko, A. R. et al. A simple genetic architecture underlies morphological variation in dogs. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000451 (2010).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarAnderson, T. M. et al. Molecular and evolutionary history of melanism in North American gray wolves. Science 323, 1339–1343 (2009).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarHaak, W. et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, 207–211 (2015).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarMech, L. D. Unexplained patterns of grey wolf Canis lupus natal dispersal. Mamm. Rev. 50, 314–323 (2020).

Article Google ScholarBaumann, C. et al. A refined proposal for the origin of dogs: the case study of Gnirshöhle, a Magdalenian cave site. Sci. Rep. 11, 5137 (2021).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarGermonpré, M. et al. Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 473–490 (2009).

Article Google ScholarDavis, S. J. M. & Valla, F. R. Evidence for domestication of the dog 12,000 years ago in the Natufian of Israel. Nature 276, 608–610 (1978).

Article ADS Google ScholarMeyer, M. & Kircher, M. Illumina sequencing library preparation for highly multiplexed target capture and sequencing. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, db.prot5448 (2010).

Article Google ScholarRodríguez-Varela, R. et al. Genomic analyses of pre-European Conquest human remains from the Canary Islands reveal close affinity to modern North Africans. Curr. Biol. 27, 3396–3402 (2017).Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ersmark, E. et al. Population demography and genetic diversity in the Pleistocene cave lion. Open Quatern., https://doi.org/10.5334/oq.aa (2015).

Stanton, D. W. G. et al. Early Pleistocene origin and extensive intra-species diversity of the extinct cave lion. Sci. Rep. 10, 12621 (2020).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarDabney, J. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15758–15763 (2013).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarGansauge, M.-T. & Meyer, M. Single-stranded DNA library preparation for the sequencing of ancient or damaged DNA. Nat. Protoc. 8, 737–748 (2013).

Article PubMed Google ScholarPoinar, H. N. & Cooper, A. Ancient DNA: do it right or not at all. Science 5482, 416 (2000).

Google ScholarKnapp, M. & Hofreiter, M. Next generation sequencing of ancient DNA: requirements, strategies and perspectives. Genes 1, 227–243 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarKircher, M. Analysis of high-throughput ancient DNA sequencing data. Methods Mol. Biol. 840, 197–228 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarOrlando, L. et al. Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse. Nature 499, 74–78 (2013).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google ScholarCarøe, C. et al. Single‐tube library preparation for degraded DNA. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 410–419 (2018).

Article Google ScholarMak, S. S. T. et al. Comparative performance of the BGISEQ-500 vs Illumina HiSeq2500 sequencing platforms for palaeogenomic sequencing. Gigascience 6, 1–13 (2017).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarFulton, T. L. & Shapiro, B. Setting up an ancient DNA laboratory. Methods Mol. Biol. 1963, 1–13 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarKorlević, P. & Meyer, M. Pretreatment: removing DNA contamination from ancient bones and teeth using sodium hypochlorite and phosphate. Methods Mol. Biol. 1963, 15–19 (2019).

Article PubMed Google ScholarKapp, J. D., Green, R. E. & Shapiro, B. A fast and efficient single-stranded genomic library preparation method optimized for ancient DNA. J. Hered. 112, 241–249 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarHarney, É. et al. A minimally destructive protocol for DNA extraction from ancient teeth. Genome Res. 31, 472–483 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarGamba, C. et al. Genome flux and stasis in a five millennium transect of European prehistory. Nat. Commun. 5, 5257 (2014).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google ScholarLi, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarRamos Madrigal, J. et al. Genomes of extinct Pleistocene Siberian wolves provide insights into the origin of present-day wolves. Curr. Biol. 31, 199–206 (2021).

Google ScholarSkoglund, P., Northoff, B. H. & Shunkov, M. V. Separating endogenous ancient DNA from modern day contamination in a Siberian Neandertal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2229–2234 (2014).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarLiu, Y.-H. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of African dogs provides insights into adaptations against tropical parasites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 287–298 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarKardos, M. et al. Genomic consequences of intensive inbreeding in an isolated wolf population. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 124–131 (2018).

Article PubMed Google ScholarLi, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 (2013).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarNí Leathlobhair, M. et al. The evolutionary history of dogs in the Americas. Science 361, 81–85 (2018).

Article ADS PubMed Google ScholarNiemann, J. et al. Extended survival of Pleistocene Siberian wolves into the early 20th century on the island of Honshū. iScience 24, 101904 (2021).

Article ADS PubMed Google ScholarLi, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarArnason, U., Gullberg, A., Janke, A. & Kullberg, M. Mitogenomic analyses of caniform relationships. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 45, 863–874 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarBjörnerfeldt, S., Webster, M. T. & Vilà, C. Relaxation of selective constraint on dog mitochondrial DNA following domestication. Genome Res. 16, 990–994 (2006).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarMatsumura, S., Inoshima, Y. & Ishiguro, N. Reconstructing the colonization history of lost wolf lineages by the analysis of the mitochondrial genome. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 80, 105–112 (2014).

Article PubMed Google ScholarMeng, C., Zhang, H. & Meng, Q. Mitochondrial genome of the Tibetan wolf. Mitochondrial DNA 20, 61–63 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarPang, J.-F. et al. mtDNA data indicate a single origin for dogs south of Yangtze River, less than 16,300 years ago, from numerous wolves. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 2849–2864 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarZhang, H. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of Canis lupus campestris. Mitochondrial DNA 26, 255–256 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google ScholarSievers, F. et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarSuchard, M. A. et al. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evol. 4, vey016 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarDarriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R. & Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarPatterson, N. et al. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics 192, 1065–1093 (2012).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarPatterson, N., Price, A. L. & Reich, D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2, e190 (2006).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarPoplin, R. et al. Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/201178 (2018).

Koch, E. et al. De novo mutation rate estimation in wolves of known pedigree. Mol. Biol. Evol. 36, 2536–2547 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Central Google ScholarChang, C. C. et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience 4, 7 (2015).

Deane-Coe, P. E., Chu, E. T., Slavney, A., Boyko, A. R. & Sams, A. J. Direct-to-consumer DNA testing of 6,000 dogs reveals 98.6-kb duplication associated with blue eyes and heterochromia in Siberian Huskies. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007648 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google ScholarHudson, R. R. Generating samples under a Wright–Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics 18, 337–338 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Keywords:

Archaeology, Ecological genetics, Evolutionary genetics, Population genetics